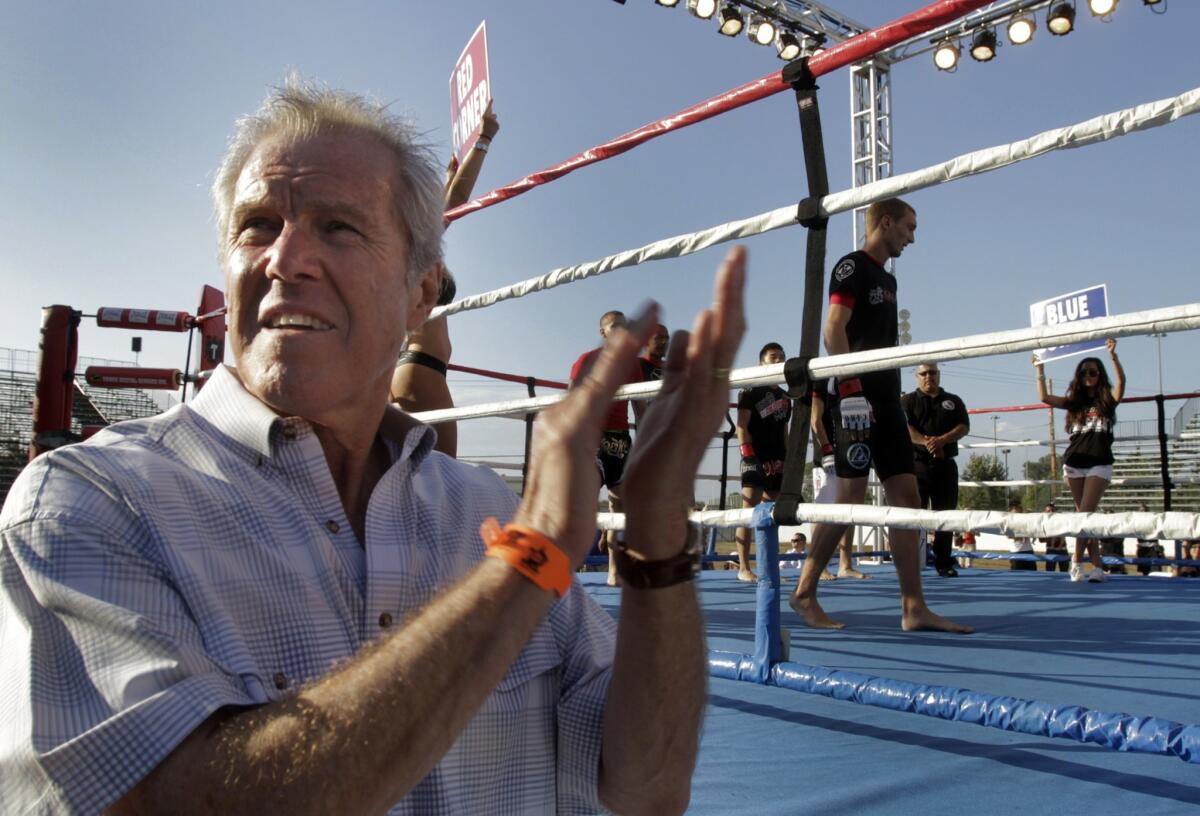

Sports promoter Roy Englebrecht takes the fights to the people

The Bee Gees are playing on Roy Englebrecht’s office radio, but the 67-year-old sports promoter has a saying taped on his wall to assure he’s not stuck in days gone by.

“Don’t judge me by my past. I don’t live there anymore.”

Southland boxing fans know Englebrecht’s name. From 1985 until 2010 he promoted a grass-roots staple of the sport, the “Battle in the Ballroom” club shows at the Irvine Marriott.

Future champions Shane Mosley, Genaro Hernandez, Johnny Tapia and Carlos “El Famoso” Hernandez all won there — Englebrecht claiming victories too, by routinely pocketing profits that climbed to about $15,000 per show at the end.

But the staying power of the quick-thinking entrepreneur — who still works 80-hour weeks in staging more fight promotions in California than anyone else — is about more than just placing a blood sport in a swanky venue.

His reinvention began in 2004 when he inspected a flier pinned to a grocery store billboard in his hometown of Newport Beach.

“Cage Fighting, Soboba Casino.”

Englebrecht knew mixed martial arts fighting was outlawed by the California State Athletic Commission, and knew Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.) had called it human cockfighting.

“But I pulled the flier off and said, ‘Why don’t I go out and see?’” Englebrecht said. “I saw these young people parking, walking close to a mile in the rain to this place.

“I’m sitting there at 6 o’clock and there were 2,500 people in this rodeo arena watching this. . . . I’m the only guy with an umbrella, the oldest guy there. I look around, see these young people — a lot of tattoos.”

MMA was an epiphany for Englebrecht, who got his start in sports in the ‘70s as the Forum’s director of promotions for Kings and Lakers owners Jack Kent Cooke and Jerry Buss.

He says he said to himself, “Holy mackerel, if people will drive to the end of the Earth on a rainy day to see this sport . . . we’ve got fans here I want.”

Englebrecht coolly stood aside and let Ultimate Fighting Championship President Dana White pay for a strong lobbying campaign that persuaded California in 2006 to sanction MMA at venues other than those at Indian casinos.

“I like the UFC, they gambled with their own money and hit a home run,” Englebrecht said. “And because they hit a home run, I’m hitting doubles.”

Englebrecht began adding MMA cards to his Marriott schedule in April 2007. Initially, he was taken aback by how an MMA fighter could bang on an opponent he had just knocked down.

“I saw that and said, ‘I like this sport, it’s all action,’” Englebrecht said. “I didn’t know the rules, but it’s all about action, the content. My fans aren’t expecting to see Manny Pacquiao or Jon Jones. They want good fights and to be entertained.”

His first MMA live gate hit $54,000, topping his then-typical $42,000 for a boxing card.

“I have the opportunity to market to two-thirds of the population now, Generation X and the Millennial,” Englebrecht said. “There’s a lot more 18- to 40-year-olds than the 50-to-75s who are the boxing crowd.”

Two years ago, nudged by his son and business partner, Drew, Englebrecht moved his fights to a spot at the Orange County Fairgrounds called The Hangar where he stages 10 “Fight Club OC” cards annually.

The Hangar is cozy but lavish, equipped with jumbo-screen televisions, private suites and more than 1,400 seats in all. The arena has a boxing ring that can be converted to an MMA cage depending upon whether the promoter is doing his Thursday boxing-MMA hybrid show or a “Hot Saturday Nights” event of MMA and the increasingly popular muay Thai fighting.

It keeps with Englebrecht’s philosophy of not overspending on facility rent. He’s proud and content with who he is, a minor league sports promoter who lives in a gated Newport Beach community.

“So many promoters think they have to be in a big arena to be a big-time promoter,” he said. “They’ll pay $30,000 to rent a 10,000-seat arena and they’re paying for 8,000 empty seats. Makes no sense.

“Paying less for the rental and selling every one of those seats with the energy that every fan is saying, ‘This is the place to be, I’m coming back.’”

Englebrecht puts on 22 shows a year in California and Washington, with boxing accounting for fewer than half of the bouts.

He’s made a career of smart, outside-the-box thinking in the business of sports. He hired a kid intern at the Forum who became Magic Johnson’s agent, Lon Rosen.

“The guy just never seemed to stop working, did innovative giveaways,” Rosen said. “He was always on, 100 miles per hour, with the energy of 10 people. And he’s still that way.”

Boxing wasn’t part of his original game plan.

Englebrecht was then buying radio broadcast rights to local men’s college basketball programs, and while trying to secure sponsorship from the Irvine Marriott, a hotel executive asked him if he believed boxing inside the hotel could draw a crowd.

“Instead of saying, ‘No,’ and going on to the sale, I said, ‘No, but why?’” Englebrecht said. “An entrepreneur should always ask why because you never know if there’s a business there.”

Twice, he has sold his promotions business, then bought it back.

First, he sold to “some guys from Newport who just wanted to date the ring-card girls, sit in the first row and drive their Ferraris to the show. . . . I re-bought it at 10 cents on the dollar,” Englebrecht said. “People just see the show and don’t realize how tough this business is.”

Englebrecht said he achieved his “brass-ring” moment when Oscar De La Hoya and Richard Schaefer, with Golden Boy Promotions, purchased his firm and ran it from 2002-04. Golden Boy is now one of the two biggest boxing promotion firms in the U.S. and sold a record $19.5 million in tickets for the Sept. 14 Floyd Mayweather Jr.-Saul “Canelo” Alvarez fight.

“It’s important in any business to learn it from the bottom up, and Roy was instrumental in teaching us,” Schaefer said. “He taught us well, being very detail-oriented and frugal. He wouldn’t waste a dollar on something like giving a fighter a per diem when he could instead pack him up a brown-bag lunch with a sandwich, Coke and chocolate bar.”

When Golden Boy outgrew the Orange County fight cards, Englebrecht took them over in 2005.

Englebrecht is also part-owner of minor league baseball teams in San Bernardino and Rancho Cucamonga, and brought arena football to Orange County, staying true to his philosophy of “over-delivering” to his customers who might expect less from a “minor league” production.

The simple charms of the business remain.

“To give a first-time fighter a $1,000 check, to see his face, knowing he became a pro athlete like Magic Johnson or Mike Trout on your show,” Englebrecht said. “It’s a very neat feeling. And I still get that feeling 28 years later.

“They have to start someplace, they don’t turn 18 and go to UFC. They turn 18 and fight for the king of the minor leagues.”

twitter.com/latimespugmire