Irvine may be at ‘end of road’ in legal fight against Musick jail expansion

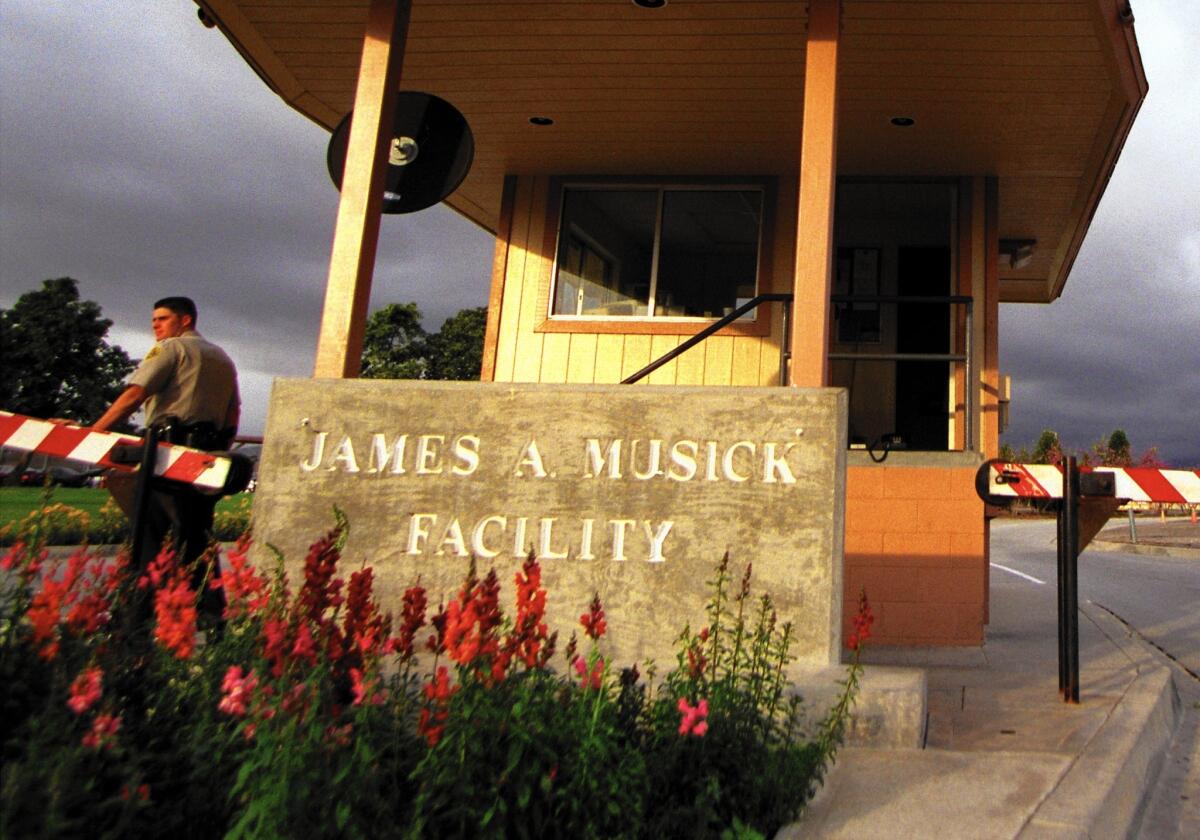

Orange County’s plan to expand the James A. Musick jail received another nod in court this month, despite concerns from Irvine city leaders who have long fought the idea.

The state 4th District Court of Appeal concluded Oct. 7 that the county’s environmental reports for the project were sufficient, rejecting Irvine’s assertion that the county had failed to properly analyze the effects of the planned $80-million expansion. The city alleged in court documents in 2012 that more study was necessary because roughly 16 years had passed since the reports were conducted.

In 1996, the county completed an environmental impact report for its plan to build out the jail to 7,584 beds by 2030. However, the project came to a halt in the early 2000s because of a lack of funding, court documents state. That changed when the state Legislature passed Assembly Bill 900 in 2007, which provided construction funding for jail expansion projects to deal with overcrowding. In late 2011, the county Board of Supervisors voted to apply for the funds.

“It is impossible to predict with precision the micro effects of various stages of construction at precise points in time without also knowing precisely when one will have the funding to implement those various stages of construction,” acting Presiding Justice William Bedsworth wrote in the 4th District’s 12-page ruling. “The best you can do is come reasonably close. That, the county did.”

The county plans to add 896 beds by October 2019 to the existing 1,322 beds at the 100-acre jail, which has housed minimum-security inmates since it opened in 1963 in an unincorporated area adjacent to what became Irvine and Lake Forest. A new visitor and staff parking area, an entrance off Alton Parkway and space for enhanced rehabilitation programs, including social services, healthcare and education, also are in the works.

The court’s decision may mark the end of a nearly 20-year legal battle between the county and Irvine, which has filed four unsuccessful lawsuits against the jail expansion during that time. Though the city could appeal to the California Supreme Court, Councilwoman Christina Shea said it is unlikely.

“We’re at the end of the road, legally,” Shea said. “We’ve spent millions fighting against this outcome and we haven’t prevailed.”

The facility, nicknamed “The Farm” because of its role of supplying fruits, vegetables and eggs to all jail kitchens in the county, originally held a maximum of 200 male minimum-security inmates. The population now includes men and women who are in jail for crimes such as driving under the influence, drug possession, burglary, prostitution and failure to pay child support.

As the jail grew, the suburban landscape of Irvine also began to expand.

The facility’s proximity to residential neighborhoods in Lake Forest and Irvine, as well as the Great Park and Irvine’s Portola High School, which is being built, is troubling for city leaders.

Though the jail is generally isolated from the rest of the community, several inmates have escaped over the years and were found elsewhere in the county.

“I don’t think there’s many people who would want to voluntarily live next to a jail,” said Irvine Mayor Pro Tem Jeff Lalloway. “In my opinion, a correctional facility that may or may not have very serious criminals is incompatible with a residential community.”