Big problem for small developments: trash pickup

In the midst of a hot real estate market — with new tracts aiming to coax neighborhood revitalization in the Westside and eclectic, urbanized housing options designed to entice young professionals — Costa Mesa City Hall is bustling these days with requests for approval of residential developments.

Yet for all the public debate, some of it fierce, about density levels, parking standards and traffic worries, planners are seeing a quirkier problem emerging: Where do homeowners put the trash cans?

City and Costa Mesa Sanitary District planners say collecting refuse has become a challenge in new housing tracts where, unlike those built decades ago, space is tight. What once was an afterthought in the planning process is gaining more attention as developers’ plans make their way through the review processes.

Because Costa Mesa is a predominantly built-out community, most of its new developments are considered infill — as in surrounded by already-established buildings. The new-development parcels are relatively small, usually only an acre or two.

So, officials say, each site plan presents its own set of challenges in coordinating trash pickup. Sometimes planners are left wondering if carts for each home — something developers want because they improve marketability — are feasible at all.

During the planning process, the Sanitary District examines the roads that will be handling, week after week, heavy-duty trash trucks. Planners also consider the logistics: How will the trucks maneuver in and out of a development?

Then there’s the intricate orchestration of trash-cart placement on small roads, within garages and in tiny setbacks.

And when it comes to new “live-work” homes planned for the Westside, planners question which kind of service should be provided — traditional, single-family-home trash carts or Dumpster-size bins — because the units are designed with the commercial elements of home offices.

Since April, the Sanitary District has reviewed more than 20 site plans. Seven have been approved.

“We’re still going back and forth with developers to find a safe, efficient route to pick up the trash,” said Scott Carroll, the district’s general manager.

*

No longer a planning postscript

The Sanitary District serves residences in Costa Mesa, as well as portions of Newport Beach and unincorporated Orange County. Most of its ratepayers live in single-family homes, where trash pickup is once a week on designated days.

The district also services multifamily apartments of four units or less.

Long-established neighborhoods of single-family homes generally have had space for trash carts to be placed on the curb during trash day and then stored in sideyards.

Residents must remove their carts from public view after trash day. Failure to do so can result in fines.

But this is proving nearly impossible in new Costa Mesa developments, said Javier Ochiqui, management analyst with the Sanitary District.

Carroll says the district has always been on top of planning sewer needs — calculating capacity, identifying the types of required piping. But more than a year ago, after the district’s contracted trash hauler, CR&R, raised concerns about difficult trash pickups within new developments, a light bulb went off.

The district realized that trash pickup and cart storage could no longer be the planning postscript in the long process for development approvals.

The district wanted to be an “equal player” in planning, Carroll said.

“We need to be in these development review committees,” he added, “and we need to give the city our input before they start approving these plans.”

The district then got involved with the city’s internal development review committee, which has been very helpful in addressing the new needs, Carroll said.

“It’s nice to be able to comment so we can work it out,” Ochiqui added.

Jerry Guarracino, Costa Mesa’s interim assistant director of development services, says the city is now requiring developers to present plans for trash pickup earlier in the process.

“It’s certainly a larger focus for us now with these new clustered, single-family developments,” he said. “In new projects this is going to be addressed in a much more comprehensive way than it may have been previously.”

Apparently, “the word’s gotten out,” Guarracino added. Some projects are coming into City Hall already designed with trash pickup in mind.

“I think most of the developers know this is an important issue, and they want to solve it,” he said. “They want to resolve it because it affects their site plan.”

No developer wants housing units cut out “because they haven’t really thought of the trash pickup,” Guarracino said. “They’re motivated to resolve the issue.”

Ultimately, every developer has to make choices, he added.

“While his customers might prefer carts, he has to decide: Is it worth losing a unit or two to allow everyone to have cart service in the project?” Guarracino said. “Or does he want to pose a different solution and keep those units? We don’t dictate that.

“He’s got know what’s more valuable in the market.”

*

‘A lot of moving parts’

Planners say there is no one-size-fits-all solution for trash cart storage and placement for pickups.

“There are a lot of moving parts with this particular issue,” Guarracino said. “There are a lot of variables on how you solve it.”

The Sanitary District’s representatives agree.

Developers have to figure where the carts will go on trash day. When factoring in the reach of the truck’s pickup arm, the carts also can’t be too close to the buildings.

“We don’t want to smash a garage door and dent it as we’re putting the cart back down,” Ochiqui said. “That’s another issue we’ve never looked at because it’s never happened before.”

Developers also have to consider that large, 30-plus-ton trash trucks will travel on a housing tract’s roads — not to mention need to be able to get into and out of that development.

It would be inefficient to make multiple egresses, not to mention dangerous if the truck has to back out onto a major street, Ochiqui said.

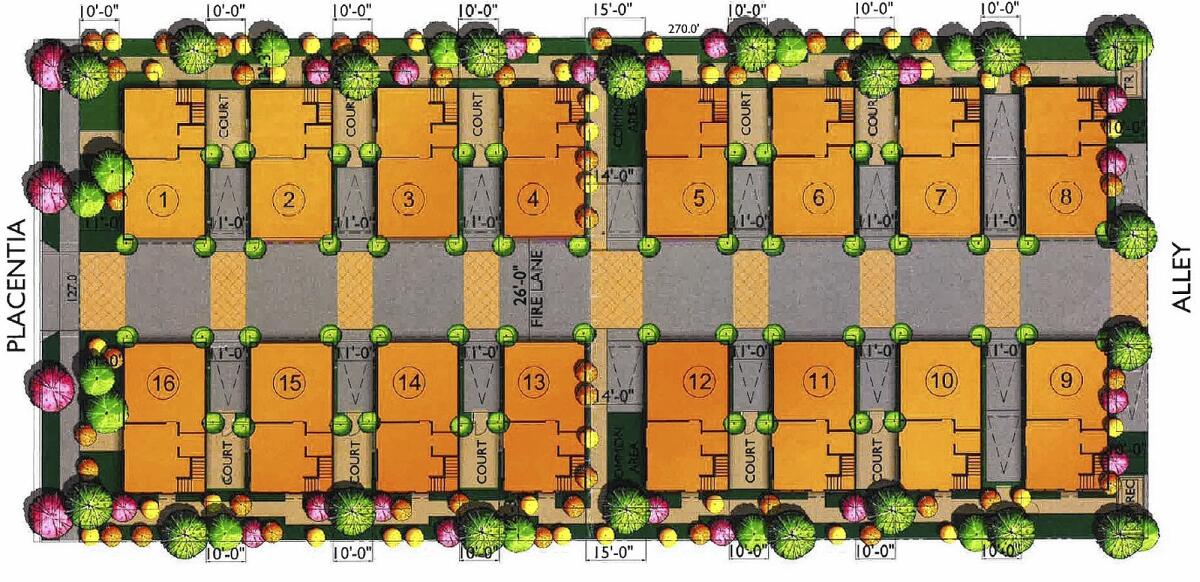

He pointed to the planning for a 16-unit live-work project at 2026 Placentia Ave., a 0.78-acre site.

The pickup arm only reaches from one side of the vehicle. Thus, it can only collect from a single side of the street, Ochiqui said.

To collect the other side, the driver would have to back out onto busy Placentia.

“That’s very, very dangerous,” Ochiqui said.

The compromise is the truck will turn around in Palace Avenue, which is essentially a large alley. Still, the district has concerns about the access gate onto Palace, particularly the possibility of malfunctions.

If that happens, “our truck is pretty much stuck there,” Ochiqui said, adding that spotting help would probably be required to ease the truck back out.

The Placentia development had planned for communal trash and recycling bins, not individual carts, to be located at one end of the lot — which meant residents at the opposite end would have had a decent walk to dispose of refuse, Ochiqui said.

During planning of an eight-unit development at 2519 1/2 -- 2525 Santa Ana Ave., a less-than-perfect compromise was reached for the 0.7-acre lot.

On trash day, the residents will put their carts at a curb that doesn’t have any houses behind it. The downside? Homes at the far end of the lot will push their carts more than 150 feet to the pickup point.

The trash truck also will be backing into the development, which isn’t ideal.

“This solution is only on their trash day,” Ochiqui said. “So if their trash day is on Wednesday, by Wednesday midnight, these carts must be gone and put away in everybody’s homes.”

If there are some straggling carts left on the curb, it’s going to be hard to know whose they are, Carroll added. The carts don’t necessarily have individual addresses on them.

The district wants to recommend that the project’s homeowners association figure out a solution, because “that would be a nightmare on us” if the Sanitary District had to enforce the rule about not leaving trash carts out beyond trash day there, Ochiqui said.

*

Commercial or residential?

The Westside Gateway project, which the council examined in June, is a case study in the complexities of trash planning.

The project at 671 W. 17th St. is larger than most new Costa Mesa developments: 9 acres, with 176 units proposed, some which are the live-work design.

As with other live-work projects, the question lingers: Will these homes use commercial-sized Dumpsters or individual carts?

“It’s harder to predict what the trash generation for live-work units are going to be,” Guarracino said.

If the live-work units require commercial trash service — which the Sanitary District doesn’t usually provide but thinks is appropriate for Westside Gateway — the number of Dumpsters on the property and where they’ll go would have to be determined.

A benefit of commercial trash, however, is that the company will provide as many pickups as needed, not just one a week.

The Sanitary District may still provide residential trash service to other portions of Westside Gateway that aren’t the live-work units. In that scenario, the developer must design a road system that can accommodate the district’s large trucks and their required turning radii, Ochiqui said.

District planners say they’ve already seen problems with Westside Gateway’s primary entrance off Superior Avenue. The parking spaces on that road aren’t leaving ample room for the trucks.

Ochiqui also sees a problem with the development’s decorative street pavers.

CR&R’s massive trucks “will chew those up,” he said.

“We don’t want to be liable [for damage] if you’re asking us to go onto your property with heavy trucks,” Ochiqui added.

The Sanitary District, though now a more involved player in trash planning, doesn’t necessarily have the power to stop a development’s approval if the trash situation isn’t figured out, Carroll said.

And if a development goes through without a compromise?

“It’ll be a nightmare,” Carroll said. “It’ll be extremely challenging for us. We could make it work, but it would just be extremely challenging.”

[For the record, 9:45 a.m. July 28: An earlier version of this story incorrectly reported the address for a planned development as 2519 Santa Ana Ave. The correct address is 2519 1/2 -- 2525 Santa Ana Ave.]