Robert V. Hine dies at 93; historian wrote of losing, regaining sight

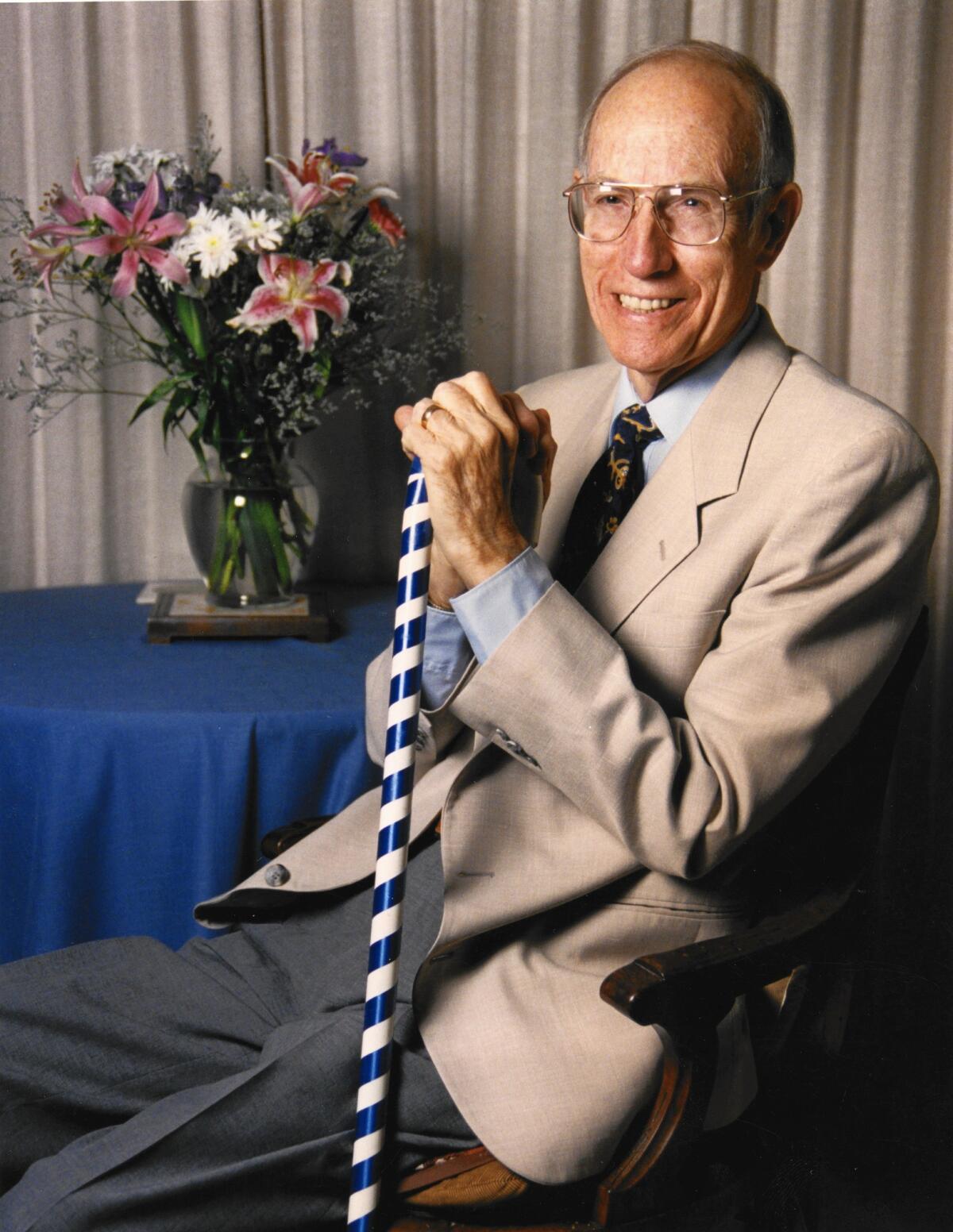

Robert V. Hine, a memoirist, novelist and prolific historian of the American West who wrote a highly praised chronicle of regaining his sight after 15 years of blindness, has died of natural causes at his Irvine home. He was 93.

Hine was a founding member of the faculty at UC Riverside, where he taught history from 1954 to 1990. His death on March 27 was announced last week by UC Irvine, where he spent part of his retirement writing books and mentoring colleagues in the history department.

An expert on California’s utopian movements and the philosopher Josiah Royce, Hine wrote or edited more than a dozen books, including an overview of the history of the American West that remains a standard college text more than four decades after its original publication in 1973.

But it was a non-academic work that brought the longtime professor his broadest public recognition.

A Book-of-the-Month Club selection, “Second Sight” (1993) was a frank, eloquent memoir of his journey into blindness and back, exploring not only his own experiences but those of other blind writers, including humorist James Thurber and poet Jorge Luis Borges.

In the book he suggested that if anyone could adapt to the requirements of a sightless life, he was such a person.

“‘Dark is a long way,’ as Dylan Thomas said, and I never will deny the blackness and the sadness,” Hine wrote. “But blind is one way to live, and creative or not I would live.”

Hine “used to say he became a part of ‘my new community of the blind,’” said David K. Glidden, an emeritus professor of philosophy at UC Riverside. “He was a positive scholar … always looking at positive things — how ideal communities work, how people try to improve not just their own lives but those they live with, how people prosper together in a community.

“That underlies a lot of his work and his personality, too. He was interested in people.”

Robert Van Norden Hine Jr. was born in Los Angeles on April 26, 1921 and grew up in Beverly Hills, where his father was a real estate developer. He was in high school when he was diagnosed with severe juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. He spent a year in bed when he was 17.

His joints were so stiff they “had to be literally broken loose by husky therapists in a warm-water swimming pool,” he wrote in “Second Sight.” After six weeks in the hospital, he learned to walk again and returned to Beverly Hills High School in time for graduation. When he walked into the auditorium to receive his diploma, “the whole audience stood up and clapped,” said his sister, Katherine H. Shaha of Draper, Utah.

He went on to UCLA, but left after he began to experience eye hemorrhages. He was diagnosed with uveitis, an inflammation of the eye caused by the rheumatoid arthritis. Later, the inflammation made it too dangerous to remove the cataracts that grew, he wrote, “like hotbeds of spurge on a humid summer day.”

His parents sent him to live in Colorado after a doctor suggested that a high altitude could alleviate the condition. Instead, his vision continued to deteriorate. He was 20 when he was told he was going to lose his sight, but his age shielded him from despair. “At the age of 20,” he wrote, “who believes a crotchety old doctor telling him that he would be blind?”

Hine forged ahead, earning a bachelor’s degree from Pomona College in 1948 and master’s and doctorate degrees from Yale by 1952.

While still in graduate school, he married Shirley McChord, a classmate from UCLA. As his eyes failed him, she became his reader and research assistant.

She died in 1996. Besides his sister, Hine is survived by a brother, Richard, of Tucson; a daughter, Allison Hine-Estes, of Santa Cruz; and a grandson.

After Yale, Hine produced his first book, “California’s Utopian Colonies.” Published in 1953 and still in print, it remains “the definitive work on the subject,” said UC Irvine historian David Igler.

Hine returned to the subject in the late 1960s, when utopian settlements were blossoming in counter-cultural California. His research on 100 modern communes was included in a new edition of “California’s Utopian Colonies” published in 1973. That same year he published his well-regarded textbook, “The American West: An Interpretive History.” He had been legally blind for two years when both books were completed.

His other books include “Josiah Royce: From Grass Valley to Harvard” (1992), two historical novels, and “Broken Glass: A Family’s Journey Through Mental Illness” (2006), a memoir about his daughter’s struggles with a serious mental disorder.

Being blind, Hine noted, had some advantages. He was not embarrassed when he conducted research in a clothing-free commune. On another occasion, he reported in “Second Sight,” he turned down a marijuana joint “because I thought it was a carrot stick.”

He worked hard to ensure his condition did not hamper him as a teacher.

Hine put lecture notes in Braille on index cards he kept in his pocket and was so adept at fingering them that many students believed he had memorized his talks. For his large lecture classes he made a seating chart in Braille that allowed him to call on individual students by name, as long as they sat in their assigned seats.

He also kept his classes lively with a multimedia approach that was novel for the time. A friend with dramatic flair recorded quotations from Jedediah Smith, Black Elk and other historical figures that Hine combined with slides and music for a Ken Burns-like documentary approach to history. Hine was so skillful at assembling the presentations that a colleague dubbed him the “Cecil B. DeMille of our department.”

In 1986, Hine had to have surgery to remove a leaking cataract that was causing glaucoma. His doctor told Hine that it was possible that after the surgery he would regain some ability to perceive light but held out no hope for anything more.

When his bandages were removed, Hine not only saw light but his wife’s silver hair. When he got home, he was dazzled by the simplest things, like the “transparent ruby redness” of the toothbrush he had thought was white.

When he returned to the classroom, the first words out of his mouth surprised him. “You’ll never know how beautiful you are,” he said to his students. “I couldn’t bring myself to explain anything more.”

Twitter: @ewooLATimes